Sunnybanks - Gone is the glory of the leafy hollow

Kathleen Gooding tells the story of a village whose fame rested on music and work

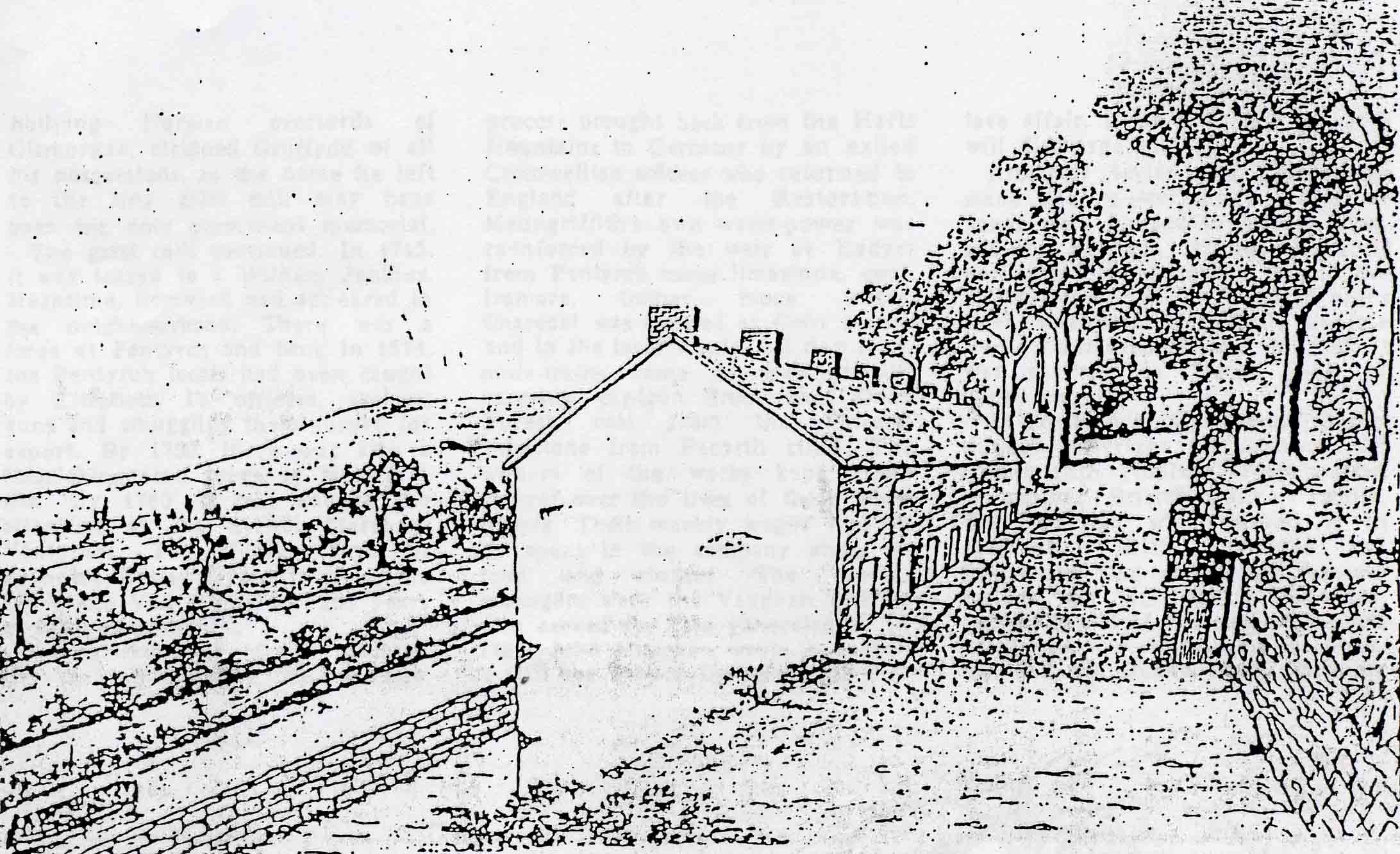

By today Sunnybanks, with its split level houses have gone. Only a heap of stones remain. Sketch by Idris Morgan

MELINGRIFFITH is a small leafy hollow, in the parish of Whitchurch, a few miles from Cardiff. Other villages radiate like spokes of a wheel: Tongwynlais, Taff's Well, Pentyrch, Radyr, Llandaff and Whitchurch. The river Taff, the Glamorgan Canal, and the artificially built feeder all flow through its narrow bottom. Today the feeder still flows under the remains of the old tinplate works, but the river is black and the once verdant canal choked with weeds.

The name is : it is a brass band, the cradle of the South Wales metal industry, it is also, in English Griffiths Mill.

Griffith, probably was Gruffydd ap Rhys, Lord of Senghenydd son of Ifor Bach, who owned a grist mill on this part of the Taff, then rich in Salmon and Trout. Corn was ground in Whitchurch and Llandaff during the 12th century when farmers from the Vale brought their corn to the mills on the weirs. In 1126, the mills at Llandaff and Ely were listed in the Concord of Woodstock.

In 1266, the De Clares, the bullying Norman overlords of Glamorgan, stripped Gruffydd of all his possessions, so the name he left to the tiny grist mill may have been his only permanent memorial. The grist mill continued, in 1715 it was leased to a William Jenkins. Meantime, Ironwork had appeared in the neighbourhood. There was a forge at Pentyrch and back in 1574 the Pentyrch locals had been caught by Elizabeth I's officers, making guns and smuggling them abroad for export. By 1750, there was also a flourishing iron forge at Melingriffith. By 1760, it had caught the attention of the Bristol Merchant Venturers. The Quaker firm of Reynolds Getley leased it from the Lewis of the Van family for 200 years at £80 per annum.

Melingriffith was ideally situated for making tinplate by a new process brought back from the Hartz Mountains in Germany by an exiled Cromwellian soldier who returned to England after the Restoration. Melingriffith's own water-power was re-inforced by the weir at Radyr: from Pentyrch came limestone, coal, iron-ore, timber, more water. Charcoal was burned at Cefn Mably and in the local woods. All day long mule-trains came to Melingriffith carrying pig-iron from the Dean Forest, coal from the valleys, limestone from Penarth cliffs. The owners of the works kept strict control over the lives of their work people. Their weekly wages had to be spent in the company shop on food and clothes. The works managers were the Vaughan family, who served for five generations. In 1785 John Vaughan wrote a letter: "I will see Walter Davies about that love affair, if he does not end it I will discharge him".

Arbitrary levies and fines were made upon a workman's wages, or goods were handed to him in kind, and his practice did not end until Parliament, amid uproar, passed the Truck Act of 1887, a hundred years later. Meantime the family tinplate works flourished so that in 1799 it was marked in Yates' map of Glamorgan.

At the turn of the century, partly through marriage connections, the Melingriffith Tinplate Works passed to another Bristol Quaker family, the Harfords, who worked it in conjunction with Partridge and Blakemore. The works had become famous for its R.G. (Reynolds Getley) brand of charcoal plates and its output was rising. The Harfords too, had the Quaker care for their workers. But they differed from Reynolds as they were principally concerned for welfare.

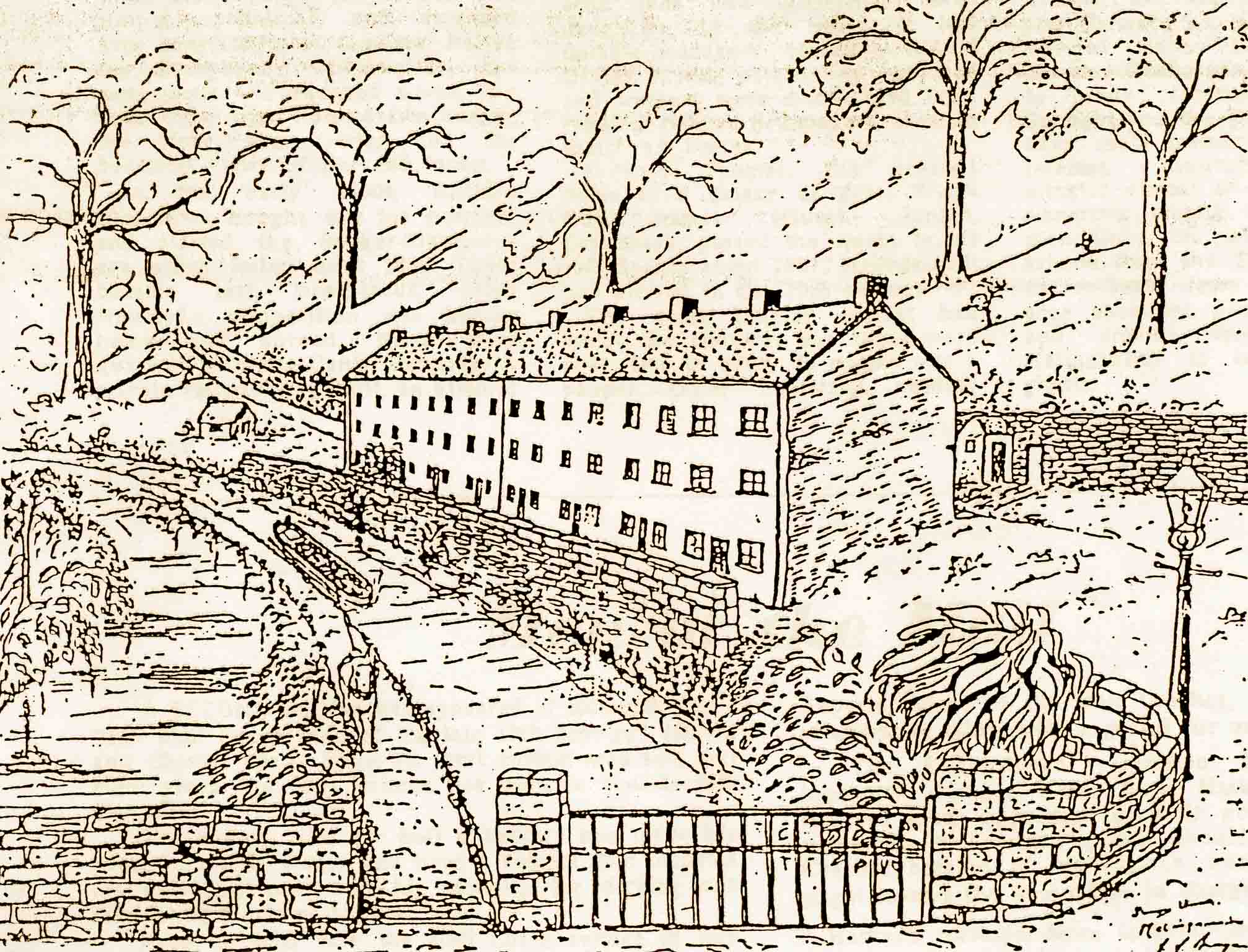

Sunnybanks was in glorious surroundings between woods and canal. Sketch by Idris Morgan

They installed a works doctor, started a friendly society, gave workers one day a year paid holiday with a feast. They were keen on education. They invited John Lancaster to Melingriffith and under his guidance opened a school for workers and their children in 1807. It is believed they built the first ever houses for workers, New Houses and Sunnybanks. These were in glorious, sheltered surroundings, between woods and canal. They were split level, their fronts looking over the canal to the Radyr hills. Young couples were given the bottom levels. When their families grew, they were moved into the larger levels.

It was a period of prosperity. Ahead lay the American Civil War and consequent boom to Melingriffith tinplates. Life in Sunnybanks was ideal: It is recorded that workers wept and were loath to leave when their tenure ended. Life was simple, communal, and extended over generations of families. Before the Sunnybanks windows lay the picturesque whitewashed works, the canal, busy with horse drawn barges, the river the feeder and the beautiful views of hill and forest. In the early 1800's, Richard Blakemore bought out his partners and started the Booker-Blakemore era which lasted until 1888. Times became less prosperous, more troubled: competition was keener home and abroad, there were quarrels with the Canal Company. A private railway was built, an attempt to boost the works by manufacturing ochre bricks failed and financial difficulties increased.

Some evidence of Sunnybanks can still be seen, one of the Pantry's which has been bricked up.

By 1879 the Company was bankrupt. Workers were unemployed, destitute and dependent on the soup kitchens which were opened. In 1881 part of the works was auctioned and sold to James Spence of Liverpool; In 1885, the remainder was auctioned to Richard Thomas of Lydbrook - Dean Forest at the price of £12,000 for the works, 30 houses, a railway and a forest plantation, and £10,000 for the raw materials, plant and machinery. In 1890, occurred the first strike over the rates paid for the Black Canada plates. After a struggle the workers won their point which was nullified by the end of the manufacture of the Black Canada plates, so nothing availed. Soon after 1896, President MacKinley's tariff whittled away Melingriffith's American trade. At its peak the works had 15 mills and turned out 12,000 boxes a week. The family interest continued so that generations sent sons and grandsons and even daughters, to the mills. It had notable managers, especially Robert Davies. A mild paternalism remained and workers were discouraged from reading radical newspapers even in their own homes.

Richard Thomas the greatest in a galaxy of Great Welsh iron names (Guest, Jordan, Crawshay), passed the works to his son, Spence about 1907, Melingriffith had arrived in the 20th century. The great Liberal revival had swept the country, but times were poor. One in every 39 people was a pauper. Other industries needing tinplates, however, were opening and the artificial booms of the world was way ahead. After the first world war the works band - was reformed and remodelled by Frank Morgan of Whitchurch, a gifted musician and himself a Melingriffith worker in his young days. In 1921, he passed it to T. J. Powell who took it to Crystal Palace and made Melingriffith Works Band a national name. Just over a decade ago, in face of new technology, Melingriffith ended its tinplate life and its connection with Richard Thomas. Part of the old, whitewashed works with its round windows is joined to a unit making blast furnace screens for Velindre, home of past owners. In the middle of the once wooded hollow, over the old iron bridge, the manager's home 'Melin was home through centuries of John Vaughan, David Merrick, Robert Davies, and last, David Williams, has been demolished, fire-extinguisher units stand on the spot. Gone too are the New Houses and Sunnybanks. Only a few sun warmed stones stand above the deserted Glamorgan Canal, gone too are the Trout and Salmon from the river Taff, the coloured narrow-boats from the canal once abundant primulas, and orchids from the banks. Melingriffith is now a place for ghosts.